تئاترِ مقاومت علیه ساختارهای پدرسالارانه

تئاترِ مقاومت علیه ساختارهای پدرسالارانه

مهرداد خامنهای

۲۴ تیر ۱۴۰۴

در نگاه نخست

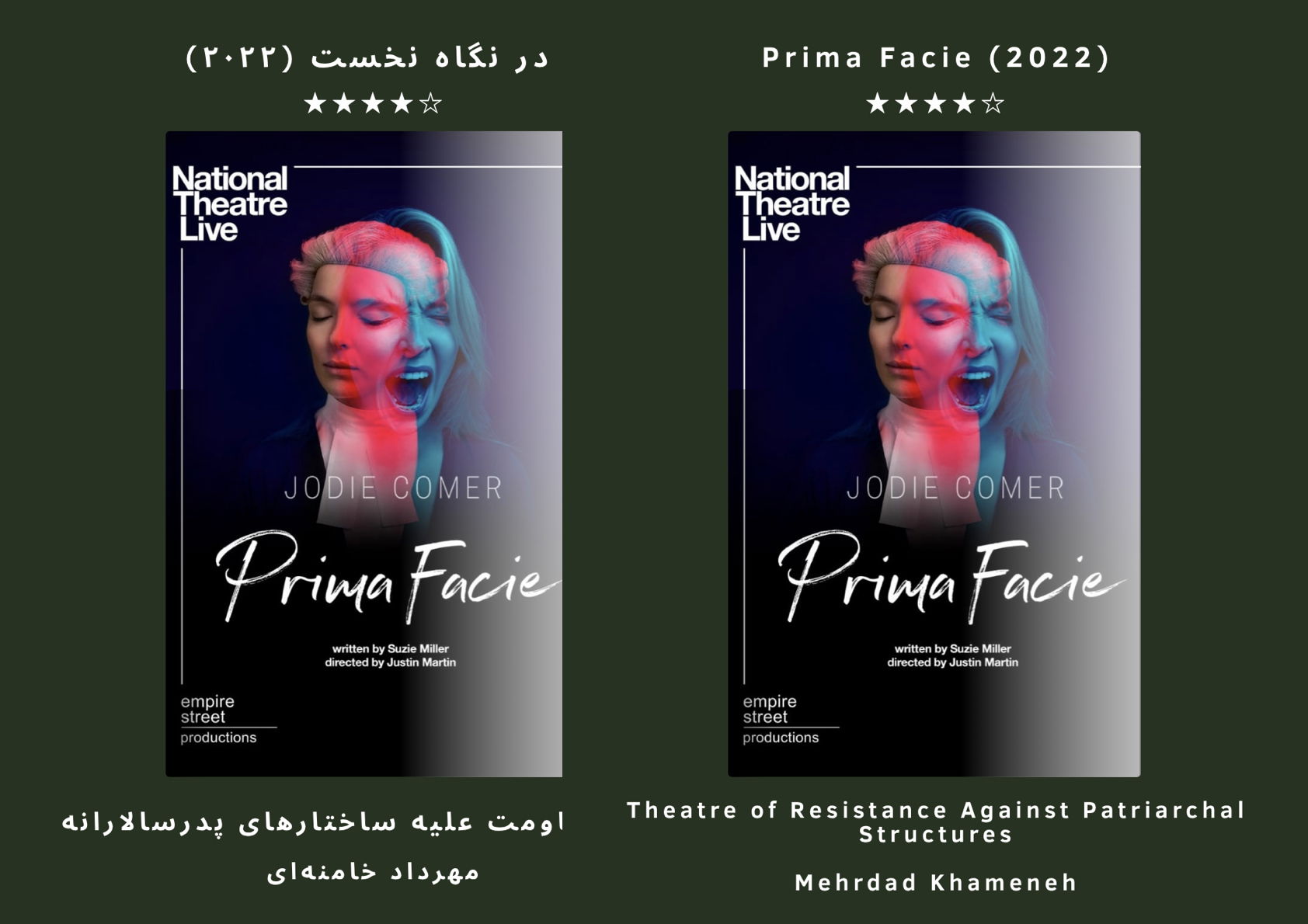

نویسنده: سوزی میلر

کارگردان: جاستین مارتین

بازیگر: جودی کومر

تولید: نشنال تئاتر لایو

سال اجرا: ۲۰۲۲

★★★★☆ (۴ از ۵ ستاره)

نمایش «در نگاه نخست» اثریست درخشان، دردناک، و عمیقاً سیاسی که مرز میان تئاتر، شهادت، و کنش فمینیستی را از میان برمیدارد. نوشتهی سوزی میلر، به کارگردانی جاستین مارتین، و با اجرایی درخشان از جودی کومر، به یکی از برجستهترین اجراهای تکنفرههای سالهای اخیر بدل شده است.

«در نگاه نخست»، که عنوان آن برگرفته از اصطلاحی حقوقیست، داستان زنیست که از دل نظام قضایی بیرون آمده تا علیه آن شهادت دهد. «تسا»، وکیلی موفق در دفاع جنایی، پس از آنکه خود قربانی تجاوز جنسی میشود، درمییابد که همان نظامی که روزگاری با قدرت از آن دفاع میکرد، چقدر در برابر صدای زن ناتوان و بیرحم است.

این نمایش نه فقط با زبان قانون، بلکه با زیباییشناسی بدن و سکوت و صدا، در ساختارهای پدرسالارانهای که در تار و پود قانون و اجتماع تنیده شدهاند، شکاف میاندازد. اجرای کومر، از لحظات پرشتاب و طنزآمیز آغازین تا فروپاشی نفسگیر انتهایی، شکلی از مقاومت عاطفیست. بدن او، صدا و لرزشش، در غیاب تمام شخصیتهای دیگر، بار جهان مردانهی اطرافش را به دوش میکشد.

این نمایش، دادگاه را به صحنه و صحنه را به دادگاه بدل میکند. از تماشاگران میخواهد نه فقط گوش دهند، بلکه قضاوت کنند، به یاد آورند، و مسئولیت بپذیرند.

در دورانی که صداهای زنان همچنان سرکوب میشود — چه در رسانهها، چه در دادگاهها — این نمایش همچون فریادیست که از درون سکوتها برمیخیزد. اینجا تئاتر خود شکلی از عدالت است.

نمایشنامهی سوزی میلر، تنها یک درام حقوقی نیست — بلکه مداخلهای فمینیستی است در زبان عدالت، افشاگر ساختارهای جنسیتزدهی نهادهای قضایی، و تجربهای تئاتری که مرز میان اجرا و اعتراض را از میان برمیدارد. این مونولوگ نود دقیقهای، تنها داستانی را روایت نمیکند — بلکه نظامی را که آن داستان را ممکن کرده، فرو میپاشد.

طراحی صحنهی این اثر فضایی کلینیکی و خشک میسازد: میز، چوبلباسی، صندلی. همین سادگی، بدنِ بازیگر را در مرکز قرار میدهد — صدایش، حرکاتش، سکوتهایش — و بدن را به میدان اصلی معنا و مقاومت بدل میسازد. طراحی نور ناتاشا چیورز و موسیقی/طراحی صوتی بن و مکس رینگهام همچون نموداری از روان زن روایتگر عمل میکنند: با گذار از اطمینان به فروپاشی، از وضوح حرفهای به بحران شخصی. زمان گسسته میشود. فضا در هم میریزد. و حقیقت — آن عنصر گریزان در دادگاه و در تئاتر — به چیزی سیال و پرسشبرانگیز بدل میشود.

جودی کومر درخشان است — نه صرفاً بهخاطر دقت فنی، بلکه بهسبب شدت اخلاقی بازیاش. او تناقضهای زنی را مجسم میکند که آموخته چگونه قانون را به خدمت بگیرد، اما خود قربانی بیعدالتی همان قانون میشود. در نیمهی نخست، او پرشور و زنده است: باهوش، مسلط، مغرور به مهارتهای حقوقیاش. اما پس از تجاوز، ناچار است وارد همان سیستمی شود که زمانی از آن دفاع میکرد — و صدایش تغییر میکند. فصاحتش به لرزه میافتد. شیواییاش در برابر نظمی که از قربانی انتظار «اثبات» دارد، نه حقیقت، متزلزل میشود.

این دگرگونی فقط بازیگری نیست — بلکه نوعی نمایش فمینیستی از چیزیست که قانون میکوشد انکار کند: آشفتگی، درد، تروما، و بدن.

میلر که خود پیشینهی وکالت دارد، دادگاه را چون صحنهای نمایشی ترسیم میکند — صحنهای که به دست سنتهای پدرسالارانه نوشته شده است. تسا، شخصیت اصلی، در لحظهای بحرانی درمییابد که «قانون دربارهی حقیقت نیست، دربارهی اثبات است.» این جمله، ساختار مردسالار نظام قضایی را افشا میکند. نمایش هیچ توهمی دربارهی منطق یا بیطرفی ندارد. برعکس، نشان میدهد چگونه قانون با منطق، احساسات — بهویژه احساسات زنانه — را سرکوب میکند و از قربانی میخواهد که شکلی از تروما را اجرا کند که برای قدرت مردانه قابلقبول باشد.

آنچه به دست میآید، تنها نقد نیست — بلکه بازپسگیری روایت است از منظر فمینیستی: جایی که قانون گوش نمیدهد، تئاتر شنوا میشود؛ جایی که دادگاه سکوت تحمیل میکند، نمایش، زبان و شهادت میآفریند.

اگر نمایش در جایی لغزش دارد، در دقایق پایانیست؛ جایی که روایت به سطح بیانیهای مستقیم و اجتماعی میرسد. این بخش، گرچه پرقدرت، گاه به دلیل شدت لحن خطابی، از تنش دراماتیک فاصله میگیرد. اما حتی همین شکستن ساختار نیز قابل خوانش فمینیستیست: میلر از پایانبندی و رستگاری سر باز میزند؛ از تماشاگر میخواهد با تردید، خشم، و پرسش سالن را ترک کند — نه با رضایت یا آسودگی.

تکنفرهبودن نمایش خود خطر تکرار و یکنواختی را به همراه دارد، اما این «تنهایی»، روشی فمینیستی است: آشکارکنندهی اینکه چگونه نهادها، زنانِ قربانی خشونت را در تنهایی و انزوا رها میکنند.

«در نگاه نخست» تئاتری فمینیستیست در شدیدترین و ضروریترین شکل خود — تئاتری که تنها بازنمایی بیعدالتی نمیکند، بلکه با آن درگیر میشود. این نمایش، همزمان روایتی شخصیست از خشونت و نیز فراخوانیست برای بازنگری در فرهنگ قضایی. در اجرای تکاندهندهی جودی کومر و متن درخشان سوزی میلر، شاهد زنی هستیم که نه فقط در برابر تجاوز، بلکه در برابر فرهنگی که سکوت میطلبد، ایستادگی میکند.

در زمانی که دستاوردهای فمینیستی در خطرند — در دادگاهها، دولتها، و حتی صحنههای تئاتر — «در نگاه نخست» خود را چون فریادی سیاسی و نقشهای برای مقاومت معرفی میکند. این اثر یادآور قدرت تئاتر است — و اینکه چهگونه میتوان با آن، شکلهای تازهای از عدالت را تصور کرد. این اثر یکی از قدرتمندترین و ضروریترین تولیدات تئاتری سالهای اخیر است.

Theatre of Resistance Against Patriarchal Structures

Mehrdad Khameneh

July 15, 2025

Prima Facie

Writer: Suzie Miller

Director: Justin Martin

Performer: Jodie Comer

Production: National Theatre Live

Year: 2022

★★★★☆

“Prima Facie” is a brilliant, painful, and deeply political work that dissolves the boundaries between theatre, testimony, and feminist action. Written by Suzie Miller, directed by Justin Martin, and performed stunningly by Jodie Comer, it has become one of the most remarkable solo performances in recent years.

Prima Facie, titled after a legal term meaning “at first sight,” tells the story of a woman who emerges from within the legal system to testify against it. “Tessa,” a successful criminal defense lawyer, finds herself a victim of sexual assault and realizes just how powerless and cruel the very system she once defended can be when it comes to a woman’s voice.

This play does not merely speak through the language of law but tears into the patriarchal structures embedded in the law and society through the aesthetics of the body, silence, and voice. Comer’s performance, ranging from the fast-paced and witty early moments to the breathless collapse at the end, becomes a form of emotional resistance. Her body, voice, and tremor carry the entire weight of the male-dominated world around her in the absence of all other characters.

The play turns the courtroom into a stage—and the stage into a courtroom. It asks the audience not only to listen but to judge, to remember, and to take responsibility.

In an era where women’s voices are still silenced—in media, in courtrooms—this performance rises like a scream from within those silences. Here, theatre becomes a form of justice.

Suzie Miller’s play is not just a legal drama—it is a feminist intervention into the language of justice, exposing the gendered structures of judicial institutions, and a theatrical experience that blurs the line between performance and protest. This 90-minute monologue doesn’t merely recount a story—it dismantles the very system that enables that story.

The stage design creates a clinical and bare space: a desk, a coat rack, a chair. This starkness centers the actor’s body—her voice, her movements, her silences—transforming the body into the primary site of meaning and resistance. Natasha Chivers’ lighting and Ben & Max Ringham’s sound/music design operate like a chart of the woman’s psyche: shifting from confidence to collapse, from professional clarity to personal crisis. Time fractures. Space dissolves. And truth—that elusive element in both court and theatre—becomes fluid and questionable.

Jodie Comer is exceptional—not merely for her technical precision, but for the moral intensity of her performance. She embodies the contradictions of a woman who learned to master the law, only to fall victim to its injustices. In the first half, she is fiery and alive: intelligent, commanding, proud of her legal prowess. But after the assault, she must step into the very system she once defended—and her voice shifts. Her eloquence falters. Her fluency stammers before a system that expects a victim to “prove” her case, rather than speak her truth.

This transformation is not just acting—it’s a feminist enactment of what the law attempts to deny: chaos, pain, trauma, and the body.

Miller, herself a former lawyer, renders the courtroom as a theatrical space—one scripted by patriarchal traditions. Tessa, the protagonist, reaches a moment of crisis when she realizes: “Law isn’t about truth—it’s about proof.” This single line exposes the patriarchal structure of the judicial system. The play holds no illusions about logic or neutrality. On the contrary, it shows how the law uses logic to suppress emotion—especially female emotion—and demands from the victim a kind of performance of trauma that is legible and acceptable to male power.

What we are left with is not just a critique—but a reclaiming of narrative from a feminist lens: where the law refuses to listen, theatre becomes attentive; where the courtroom imposes silence, performance creates language and testimony.

If the play slips anywhere, it is in its final minutes, where the narrative reaches the level of direct political statement. Though powerful, this section, with its rhetorical intensity, sometimes distances itself from dramatic tension. Yet even this structural break can be read through a feminist lens: Miller refuses closure and redemption; she wants the audience to leave with doubt, anger, and questions—not comfort or catharsis.

The one-woman nature of the show always risks repetition and monotony, but here, “aloneness” itself becomes a feminist method—revealing how institutions abandon victims of violence in isolation and solitude.

Prima Facie is feminist theatre at its most urgent and uncompromising—not just a representation of injustice, but an engagement with it. This play is both a personal story of violence and a call to reconsider our legal culture. In Comer’s searing performance and Miller’s incisive script, we witness a woman who stands not only against rape, but against a culture that demands her silence.

In a time when feminist gains are under threat—in courts, in governments, even on theatre stages—Prima Facie rises as a political cry and a blueprint for resistance. It reminds us of the power of theatre—and how it can be used to imagine new forms of justice.

This is one of the most powerful and necessary theatrical productions in recent memory.